Every teacher has one. A story about a kid who wouldn’t read. A kid consumed with video games or other distractions, who just couldn’t see how reading can light a powerful fire within.

For Julia Dudley-Haley ’11, M.S. ’14, his name was Antwon, a star football player in her class at Appomattox Middle School who had never read for pleasure, with a predictable effect on his prospects for future academic success.

A former science teacher-turned reading specialist (a Longwood professor had encouraged and helped with the transition), Dudley-Haley found the traditional techniques went nowhere. One-on-one conversations, gentle encouragement—nothing worked. And Antwon was hardly alone in Dudley-Haley’s class, where—as so often, these days— reading seemed overwhelmed by the relentless competition for students’ shortening attention spans.

“Teachers—especially reading teachers—are up against major challenges everywhere they turn,” said Dudley-Haley, now the divisionwide middle-school literacy coach for the city of Lynchburg. “Antwon was like a lot of kids, not only distracted by video games, sports and friends, but also not realizing that there are books that tell stories he can connect to—that not every book on the shelf is boring or out of touch.”

To reach him, Dudley-Haley knew she would have to dig deep into her own teaching experience and much of what she learned as an undergraduate and graduate student at Longwood. She knew the answer would be part art, part science—and unique to Antwon, because every kid is different. But she was determined to figure it out.

She was determined to make Antwon a reader.

IN IT TO WIN IT

It would be easy to despair about the future of reading.

The pull of digital media is unrelenting, and so is the seeming push to structure every moment of children’s time in the classroom and beyond—play dates, sports practices, band camps. Reading books, a solitary and often time-consuming act, is easily pushed aside.

Even as more students graduate from high school, the national illiteracy rate has remained essentially unchanged for 20 years. An estimated 14-20 percent of the adult population reads at only an elementaryschool level. At home in Virginia, illiteracy rates in some of the most economically depressed regions approach a quarter of the adult population, making the school-to-prison pipeline a stark reality: Prisons can predict with a fair amount of accuracy the number of beds they will need in the coming decades by examining the fourth-grade literacy rate.

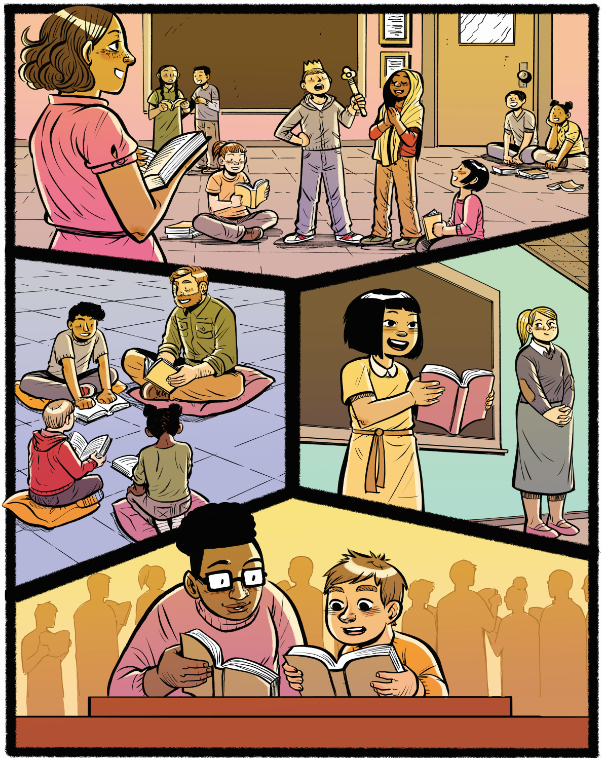

But Longwood is hardly surrendering to the tide. In fact, it’s becoming a leader in advancing the cause of childhood reading—in a wide range of interlocking endeavors. Nearly two centuries after its founding, Longwood has grown widely beyond its teacher-training roots. But its various pathways into the teaching professions remain the largest programs on campus, and it remains a center of excellence, highly regarded across the commonwealth as a wellspring of great teachers.

Longwood faculty research is on the cutting edge of international efforts to encourage reading and informs new and imaginative ways the university is preparing the next generation. Getting preschool students ready to read” is a front-and-center focus at Longwood’s new childhood development center, which opened in October.

And finally, there is Longwood’s burgeoning partnership with the Virginia Children’s Book Festival, which it hosts each October. The festival has brought close to 20,000 school children to campus, emerging in just four short years as one of the premier children’s literature festivals anywhere.

“Reading is the most fundamental skill we can instill in a child,” said Dr. Angelica Blanchette, assistant professor of education and co-coordinator of Longwood’s reading, literacy and learning graduate program. “It really is that simple. It’s the key to unlocking just about anything anyone ever wants to learn. Studies consistently show that children who can read on grade level and build an enjoyment of reading are healthier, happier and more successful. That’s why it’s so critical that we not only study the most research-based techniques, but send out teachers—from pre-kindergarten to high school—who are equipped with that knowledge and the experience of putting it into practice. Too many learners come to our classrooms and don’t see themselves as readers. Longwood teachers and literacy specialists are prepared to tackle that challenge and are turning the tide one school, one classroom, one child at a time.”

LEUYEN PHAM, a first-time participant in the Virginia Children's Book Festival this year, is an award-winning author/illustrator of nearly 60 children’s books. Her books include God’s Dream, written by Archbishop Desmond Tutu; the New York Times best-selling series Freckleface Strawberry, written by Julianne Moore; and Grace for President by Kelly DiPucchio. Some of her most recent work can be seen in the pages of Vamperina Ballerina.

'Teachers—especially reading teachers— are up against major challenges everywhere they turn.'

JULIA DUDLEY-HALEY ’11, M.S. ’14, Divisionwide Middle-School Literacy Coach, City of Lynchburg

DARING TO BE DIFFERENT

One of Dr. Katrina Maynard’s favorite assignments for liberal studies students who hope to become elementary and middle-school teachers is asking them to create a class presentation about how the six language structures—phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics and pragmatics—work independently and together to build literacy. “Every year, each group does something different,” said Maynard, associate professor of education and coordinator of the elementary and middle-school education program. “Some represent the language structures as interlocking puzzle pieces, petals making up a complete flower or a blueprint of a house to explain the relationship between concepts.”

That variety is precisely the point. “What’s really interesting is that it mirrors what they will face in their own classrooms: a room full of children with different approaches to learning,” she said. In their own coursework, Longwood students get a deep understanding of all the latest research and a grasp of literacy development in all its dimensions. But there’s one big idea at the cutting edge of teaching reading: an intensely personal approach that changes based on the skill level, personality and interests of each child in the classroom.

Thinking about Antwon and his classmates, Dudley-Haley knew she had to develop a fresh way of approaching reading lessons that would allow her class to blossom. An idea took shape in her head: “book talks.” “I let my students choose the books they wanted to read, which is walking out on a limb that not a lot of teachers are willing to try,” she said. “But it’s important, especially if we are going to adopt a culturally responsive approach. Then, as they read the books, we worked in small groups—where kids had similar literacy problems—to develop better skills using those books as the working text. And finally, I asked them to make a presentation and sell their book to their classmates.”

Those presentations became the hot ticket in class: Everyone was chomping at the bit to pitch their text, using whatever means of expression they wanted. If it seems similar to Maynard’s favorite lesson each year, that’s because it is: Each student takes an individual approach to show what they know about the book they just read.

For veteran teachers, there can be natural skepticism about changing an approach that has been ingrained for so long. In her current role as divisionwide literary coach, it’s a challenge Dudley-Haley faces frequently. “There was one teacher who was my biggest skeptic,” she said.

She kept insisting there had to be a catch to guided reading—where students read in small groups so we can work on different skills. After I modeled the technique, we co-taught and she led a lesson by herself. She was almost in tears when she told me there were kids in her class she heard read for the first time all year. If she had never broken them into smaller guided reading groups, she’d never have had the opportunity to hear them.”

Of course, no amount of theory or conceptual learning is adequate without real classroom experience. That’s why every Longwood graduate who enters a classroom comes armed with more than double the number of state-required field practicum hours.

That means micro-teaching in small groups so pre-service teachers can practice their lessons and incorporate peer and professor feedback. It also means intense debriefing sessions with faculty members and other teachers after each lesson to discuss what worked and what might be done differently. And it means a chance to immediately practice the methods they are learning on campus—honing their skills to become more effective teachers.

“There’s a time-tested process where we professors model current teaching methods, then pre-service teachers reflect on those lessons before teaching their own lessons in a classroom,” said Maynard. That process, repeated and repeated over years on campus, has given our alumni such firm footing in their own classrooms.”

Veteran teachers will also tell you that reading starts before first grade. Children develop the habits of reading when parents read to them at night, and with the right preschool teachers. Longwood this fall launched the Andy Taylor Center for Early Childhood Development, where preschool children from area families are encouraged to explore their surroundings according to their own interests. Alphabet principle and phonetic awareness are two key parts of the instruction at the center.

But it’s much more than another preschool option for parents. Plans are to make the Taylor Center an important resource for Longwood students interested in becoming preschool teachers themselves. A proposed early childhood teacher preparation program would extend to even younger children the model-reflection-teaching process that has been so successful at Longwood for more than a century.

WHEN AUTHORS ARE THE ROCK STARS

If you ever start to harbor doubts about the power of reading— to wonder if kids are still passionate about books and transformed by them—simply step onto Longwood’s campus during the Virginia Children’s Book Festival.

They come by the thousands, brown-bag lunches often in hand, arriving on yellow school buses from across Virginia and—as of this year— North Carolina and other states, too.

They squeal with delight at the chance to meet in person the authors of the books many of them already know and love. The authors who speak, demonstrate and perform are a veritable “Who’s Who” of children’s literature—Judy Blume; Arthur creator Marc Brown; recent Newbery and Caldecott award-winning artists like Matt de la Pena, Sophie Blackall and Javaka Steptoe; and inimitable and ever-popular characters like Todd Parr (author of The I Love You Book, The Earth Book and The Thankful Book).

These authors bring their own expertise in getting kids to read. If Longwood’s faculty are masters of the science behind literacy, the VCBF is a vibrant festival celebrating the art—the creative jolt of energy—that is always part of the recipe of success.

“When I’m deciding what to write, I have to inhabit the space of a teenager, recalling those particular fears and sense of humor, and then tell the truth of that experience,” said Meg Medina, an award-winning writer whose 2016 young adult novel Burn Baby Burn was named to the National Book Award longlist and who made her second appearance at the VCBF this year. “That’s the tricky part: When we become adults, we want childhood to be something different than it was. It’s not all learning how to ride a bike and building forts. And the more you can put your finger on what’s authentic about childhood, that’s where the connection is.”

To a person, these authors and illustrators say the key to success in getting kids to read is humor. Kids, after all, love to laugh and play and be surprised. It’s how they deal with tense situations, serving as the valve on the pressure cooker in many situations.

Our brains, says Dr. Catherine Franssen, associate professor of psychology and director of the neurostudies program at Longwood, are wired from the beginning to smile and produce giggles. It’s not behavior that has to be learned—having a sense of humor is as natural as the hair on your head—or, as Newbery Honor-winning author and 2017 VCBF presenter Adam Gidwitz might say, as natural as a fart from a dragon.

“Humor is the salt in a recipe,” said Gidwitz. “Salt makes all the other flavors more intense. What makes kids laugh ... could be something unexpected, like a character getting his head chopped off, then picking it up and acting like nothing happened. Or something a little gross, like a farting dragon. But when kids are laughing, it means they have opened themselves up to what is happening on the page, and you might as well put something important in there.”

The VCBF’s rise has been meteoric; with thousands of children, teachers and parents on campus, it can be hard to believe the festival is just four years old. Each year it also connects more deeply with programming around the university, including Greenwood Library, the Longwood Center for the Visual Arts, the Moton Museum, the Taylor Center and faculty from a range of academic departments.

One of the VCBF programs, which seeks to combine reading skills with the popular computer game Minecraft, bridges the technology gap that many parents and teachers struggle to overcome. Festival attendees read a story together, then set off to re-create the world of the book within the game.

Pressures from technology are not lost on authors and illustrators, says Sophie Blackall, who won the 2016 Caldecott Medal. It’s up to authors and illustrators, she says, to engage on the kids’ level and never lose sight of their experience in the world.

“Everything has changed since I was a child,” she said. “It’s easy to forget that and easier still to dismiss it. But for these children, the world is normal, and it’s up to us to meet them where they are. That means, for me, to think about book illustrations in a different way, to write books that are engaging from the first word and to try and integrate their experiences into the things we write.”

For Medina, that means acknowledging the process of growing up is thrilling and horrifying all at the same time. There are moments that are hard to deal with, or that children don’t understand, or want to celebrate, and every kid looks for a companion to consider their own situation. Books are very often the best companion.”

Anyone who has been on campus during the VCBF and seen the children come alive during a session with an author or illustrator knows that the fight for reading is far from over. At Longwood, it continues with the daily lesson, punctuated by one of the most colorful and exciting events of the year, that reading is the key to unlocking a child’s future.

TODD PARR, who has participated in the Virginia Children’s Book Festival since its inception, is the best-selling author and illustrator of more than 30 children’s books about love, kindness and family, including The I Love You Book, The Feelings Book and It’s Okay To Be Different. His books are available in more than 15 languages throughout the world.

'When kids are laughing, it means they have opened themselves up to what is happening on the page.'

ADAM GIDWITZ, Newbery Honor-winning Author

THE MAGIC OF THE RIGHT BOOK

For Antwon, that reluctant eighth-grade football star, that companion came in the form of a book written by Mike Lupica, the provocative New York Daily News sports columnist who found a second calling as a young adult author writing fiction about teenage athletes. Antwon had been through book after book—with little interest—until he found the one with the quarterback on the cover.

A quarterback, like him. “He got sucked in,” said Dudley-Haley. “It was one of those electric moments that made me remember all the times in my own life that I had lost all sense of time in the middle of a book. He simply couldn’t put it down. And when he finished—faster than he had ever read a book before—he couldn’t wait to give his book talk. And when he let loose in front of his classmates, they all bought in—everyone wanted to read everything Mike Lupica had ever written.

“It was one of those moments that, for a teacher, it all comes together in this burst of magic. That’s what’s so special about reading.”

Leave a Comment