Like many good stories, this one begins with a legend. Here’s how it goes. It was 2001, and Ruffner Hall was on fire. The flames spread quickly in every direction. For everyone watching, it was as though the heart of Longwood was being destroyed. The fire spread quickly toward the historic Colonnades, where countless graduation pictures have been taken and CHI Walks initiated, and there was nothing to stop it.

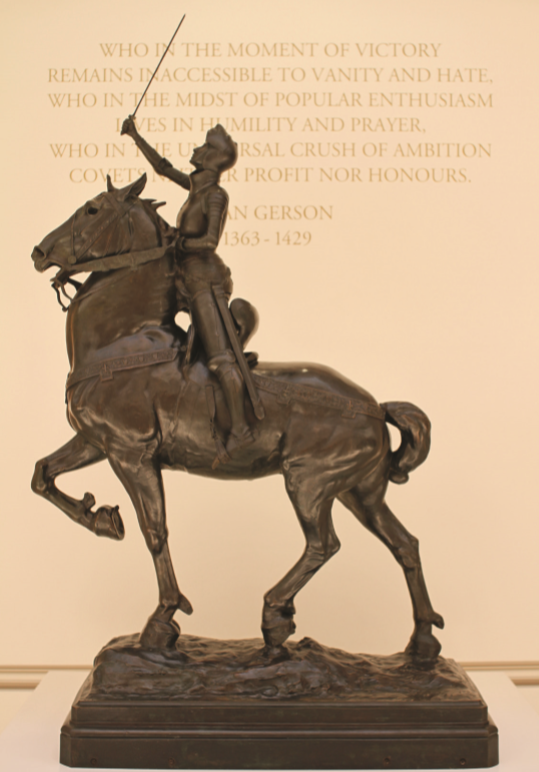

Except there was. For there stood Joan of Arc astride her horse, sword held high— Joanie on the Pony—glowing bright red from the heat, fighting back the flames from burning more of her beloved college. And somehow, almost miraculously, the Colonnades were untouched.

As legends go, it’s a pretty good one. But, of course, it would be Joan who kept the flames at bay. Joan the beloved patron hero of Longwood, the inspiration for students, forever the First Lady of Longwood.

A HERO FOR THE AGES

“Here she will stand for a thousand years,” said President W. Taylor Reveley, just before the newest statue to Joan of Arc was dedicated in November, more than a century after the first sculpture was placed under the Rotunda.

That the story of a French peasant teenager who helped drive the English out of France has survived for more than six centuries is remarkable. Perhaps even more remarkable is that the story continues to inspire devotion today.

She was only 19 when she was burned at the stake, having been turned over to the English and convicted of heresy and cross-dressing in a politically rigged trial. Her death was only two years after she arrived in Orleans, a French city that had been under siege by English forces for a year.

Claiming that God had instructed her to lift the siege, she led French forces to victory nine days later.

It’s a story of courage and faith and leadership, and one that resonated particularly strongly in the early 20th century, as women across the globe staked new ground for themselves.

A GIFT FROM THE CLASS OF 1914

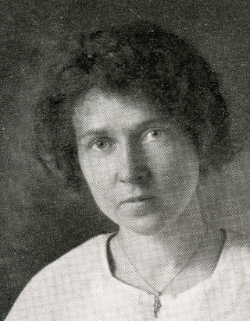

In 1914, President Joseph Jarman was looking for a statue to put under the Rotunda. At the same time, Maria Adams Bristow Starke, class president, was looking for a subject for her commencement speech.

Longwood didn’t go looking for a heroine, but the time was ripe to find one. In 1914, women’s suffrage was in full swing across the country. Several states had already granted women the right to vote, and within five years Congress would pass the 19th Amendment. As the world erupted into global war, women found themselves in new roles.

On campus, Starke, anxious about her upcoming commencement speech and, suffering from writer’s block, turned to her favorite English professor, Dr. James Grainger, for help. The pair took stock of the world and settled on a timely theme: Leadership of Women.

Starke could have used as a subject any number of women’s suffrage heroines: Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Alice Paul. Instead, for reasons we may never know, she chose Joan of Arc, who at that time was undergoing a worldwide resurgence. France had marked the 500th anniversary of her birth, and she was about to be canonized by the Catholic Church.

Quickly the choice became more than just a commencement speech theme.

“At the same time that I was struggling for a theme, the Senior Class was deliberating over an appropriate gift to the College,” Starke wrote in a letter years later. “Fortunately, we had learned from Dr. Jarman that he had long wished to have a suitable piece of statuary for the Rotunda. After much research and several consultations with Dr. Jarman, the class of 1914, on his recommendation, decided that their gift to the College would be a statue of ‘Joan of Arc Listening to the Voices,’ as sculptured by Chapu.”

That summer, the seated figure of Joan of Arc, eyes gazing up at the heavens, hands clasped in pious prayer, her simple dress cascading in gentle folds onto the rock where she is resting, arrived on campus and was placed under the Rotunda. Soon she would be known on campus as Joanie on the Stony.

As an icon, Joan of Arc is the ultimate blank canvas, taking on all brushstrokes, often reflecting back what people want to see in her. She has, in fact, stood as a symbol for opposing forces throughout the last 600 years, sometimes simultaneously: French nationalism, French defeatism; the Catholic Church, opposition to the church; patriotism, emancipation; audacity, largesse; the far political right, women’s liberation; biblical literalism, LGBTQ+ rights. She’s Saint Joan, canonized by the same church that convicted and killed her five centuries before.

“She is both used and abused by a great many groups,” said Dr. Kelly DeVries, a professor of medieval history at Loyola University in Maryland, who authored a seminal work about Joan in 2011 and spoke at Longwood’s annual Medieval Conference that year. “Historically speaking, what we have is an incredibly brave, spiritually obsessed, devoted, zealous woman who changed history. It never happened that way before and hasn’t happened that way since. But her story is so powerful and so inspiring that a lot of different types of people see themselves in her, and that’s why she endures more than six centuries after her death.”

'After much research and several consultations with Dr. Jarman, the class of 1914, on his recommendation, decided that their gift to the College would be a statue of ʻJoan of Arc Listening to the Voicesʼ... .ʼ

Maria Bristow Starke, 1914 class president

'Defining [Longwood’s] identity and affirming itself as a college for women … has a lot to do with why Joan of Arc not only was chosen in the beginning, but why her story resonates so powerfully through generations of students.'

Dr. Kat Tracy, professor of medieval literature

This is perhaps the most important realization in understanding how a 15th-century French teenager became the defining cultural touchpoint at a small teachers college in Southside Virginia. The women there saw something of themselves in her.

ANOTHER JOAN COMES TO CAMPUS

For 13 years, Joanie on the Stony presided over Longwood’s women. Her central place under the Rotunda made her, practically, a landmark in the hub of daily campus life, which bred a deep familiarity with her figure. Students met at the statue before heading to the dining hall, between classes or before heading downtown. Unlike other women’s colleges around the state that had the same Joan of Arc statue—Radford, James Madison, Mary Washington—the figure stirred something deep inside students at Longwood. Something that demanded more of Joan of Arc.

“Part of this puzzle is Longwood itself,” said Dr. Kat Tracy, professor of medieval literature at Longwood. “It’s the third-oldest public university in Virginia and has always been its own place, unaffiliated with any other university, so it was free to develop its own culture. Defining its identity and affirming itself as a college for women—especially with Hampden-Sydney right down the road—has a lot to do with why Joan of Arc not only was chosen in the beginning, but why her story resonates so powerfully through generations of students.”

An early note from CHI to freshman students illustrates just how campus burned with the intensity of feeling:

This your challenge. With the spirit of Joan as your guide, seek to grow in mental stature as you quietly contemplate the advice, the wisdom, the inspiration of your administration, your faculty, and especially of your friends—the upperclassmen, the girl next door, the roommate … Let the boundless faith of Joan permeate your life and spur you on to the highest endeavor. Dream, hope, plan with her, and with greater maturity go on to build the tangible out of your intangible dreams. To feel the spirit of Joan of Arc and to sense her vision of the ideal is to enlarge the spirit of the college and to watch it grow.

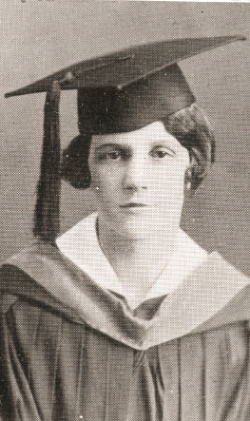

Enter Lucy Hale Overbey ’27.

Since 1914, students like Overbey had devoted countless hours to the study and compilation of everything Joan of Arc. Hundred-page scrapbooks were filled with clippings, original poetry, photos and postcards of their heroine. They professed their devotion to her example in lengthy Rotunda columns. They dedicated page after page of the Virginian yearbook to her spirit.

So strong was this devotion that Overbey and her fellow members of the Joan of Arc chapter of Alpha Delta Rho, a national service sorority, decided they simply must have another statue of their heroine on campus. The one that caught their eye was not an image of the pensive teenager they passed in the Rotunda every day, but of a strong, straight military hero.

What is most striking about the Joan of Arc depicted in Anna Hyatt Huntington’s triumphant sculpture is not the scale, her position astride her horse or even her military armor instead of a dress. It’s her posture.

‘To raise [the money for the statue] means that we will have to make the greatest sacrifices we have ever made. However, each of us is fired with such a keen desire to have this statue that nothing can stop us... .ʼ

Lucey Hale Overbey, Class of 1927

‘She taught me what's possible. It's a concrete lesson that tasks that seem insurmountable aren't necessarily so. People saying “you cannot” is no reason to turn back.ʼ

Marianne Moffat Radcliff ’92

But perhaps most importantly, they became the continuity between generations, despite radical changes to the college: a shift to liberal arts education in the 1940s, explosive growth in student enrollment in the 1960s, the full admittance of male students in the 1970s and transition to Division I sports in the 2000s. Through it all, there was Joan.

In 2014, as architects and campus planners considered projects to shape Longwood for future generations, they decided to commission a large, dramatic piece of public art to be installed at the southern end of Brock Commons, tying that part of campus to the historic northern core. The subject of the monument was never in question. How could it be anyone other than Joan of Arc?

Renowned neoclassical sculptor Alexander Stoddart, who was chosen to create the newest Joan of Arc monument at Longwood—the third and largest sculpture, installed in November 2018 at the southern end of Brock Commons—was inspired by the commission.

“I got a complete vision of the monument instantly,” he said. “Very little has changed since that moment. It’s similar to a melody that a composer hears in his head: It comes out intact, and the composer tries to catch up to what already exists.”

Unlike the two Joans that have taken on iconic status in the last century, Stoddart’s Joan, while neoclassical in form, is intentionally of the 21st century. Her deliberate androgyny, unflinching power and forward-moving posture reflect a time when, globally, women are again staking new ground.

“She’s not meant to be cute or sweet,” said Stoddart. “She’s meant to be a daunting figure. I wanted to make her what we Scots would call a bit gallus. There’s no real English equivalent, but it’s sort of self-confident, daring, even cheeky. Think Steve McQueen or James Cagney from those old movies. But if you think about it, she was a teenage girl in charge of 5,000 men. She’d have to be more than a bit gallus to pull that off. Look at what’s happening in the world today with gallus women taking charge of their own lives. I wanted Joan to reflect that.”

During the dedication in November 2018, when the Longwood community first saw the 15-foot-tall monument in full form atop its pedestal, it was Marianne Moffat Radcliff ’92, Board of Visitors rector, who put her finger on the great lesson of Joan and why she has endured on campus.

“As tragic as her ending was, her accomplishments are nearly unmatched,” she said. “She taught me what’s possible. It’s a concrete lesson that tasks that seem insurmountable aren’t necessarily so. People saying ‘you cannot’ is no reason to turn back. These are life lessons worth learning.”

Perhaps that’s why 104 years after Joan of Arc first arrived on campus, she is as much a symbol of the university as the Rotunda itself, part of the fabric of the place, an inextricable cultural touchpoint for students and visitors.

Perhaps that’s why 104 years later, Joan of Arc is Longwood. If she is a blank canvas, generations of Longwood students have painted her blue and white, casting onto her their love and devotion to their alma mater.

Leave a Comment